“Nothing like the Great Enrichment of the past two centuries had ever happened before. Doublings of income—mere 100% betterments in the human condition—had happened often, during the glory of Greece and the grandeur of Rome, in Song China and Mughal India. But people soon fell back to the miserable routine of Afghanistan’s income nowadays, $3 or worse. A revolutionary betterment of 10,000%, taking into account everything from canned goods to antidepressants, was out of the question. Until it happened.” –Deirdre McCloskey

INSIGHT

Conquering Knowledge Loss

Robert Hendershott and Don Watkins

One of the unheralded achievements of the modern world is that we have conquered a challenge that plagued the ancient world: the problem of knowledge loss.

You’re a farmer in some remote region of Europe 3,000 years ago. You come up with a better way to grow beans. Maybe you tell your neighbors, and your little town becomes prosperous. You’ve got beans coming out your ears. Then a volcano wipes out your town and the world is bean-deprived for a few millennia.

The less knowledge propagates, the more likely it will be lost.

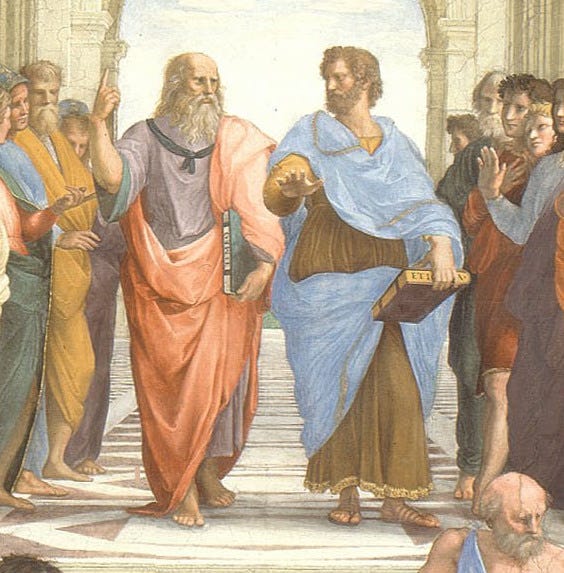

Take some real-life examples. Aristotle makes discoveries in nearly every field of human knowledge (and essentially creates some fields). Then, with the fall of antiquity, virtually all of his work is lost to the West. By the time his works are rediscovered 1,000 years later…well, here’s how Richard Rubenstein describes it in his book Aristotle’s Children:

Once upon a time in the West, in Spain, to be exact, a collection of documents that had lain in darkness for more than one thousand years was brought to light, and the effects of the discovery were truly revolutionary. Aristotle’s books were the medieval Christian’s star-gate. For Europeans of the High Middle Ages, the dramatic reappearance of the Greek philosopher’s lost works was an event so unprecedented and of such immense impact as to be either miraculous or diabolical, depending on one’s point of view. The knowledge contained in these manuscripts . . . was remarkably comprehensive. Some three thousand pages of material ranging over the whole spectrum of learning from biology and physics to logic, psychology, ethics, and political science seemed to be a bequest from a superior civilization. . . .

For medieval Christians, reading his books for the first time was like finding a recipe for interstellar travel or a cure for AIDS inscribed on some ancient papyrus.

Humanity got lucky with the rediscovery of Aristotle. Other knowledge is never rediscovered, but has to be recreated. The Egyptians built the pyramids, and until a few years ago, we had no clue how they did it. Ancient Rome’s shockingly modern sanitation system, which included working faucets, vanished after Rome’s fall. Humanity didn’t come anywhere close until the 18th century. We will never know how much more quickly humanity would have progressed if this knowledge had not been lost.

Progress consists of knowledge building on knowledge. Today we worry about the rate at which we can discover new knowledge. In the past, the potential for losing knowledge was humanity’s greatest vulnerability. Knowledge existed but it was concentrated: in the libraries and universities of a few major cities, in the minds of a few gifted scientists and craftsmen.

In the modern world, by contrast, knowledge is diffuse. The Internet is like a turbo-charged copy machine that takes knowledge and ideas and propagates them around the entire globe in a fraction of a second. Even in many nightmare scenarios, like a global loss of electricity, the planet is filled with universities, libraries, and millions of minds in every field possessing advanced knowledge. Rome fell and we went into a dark age. There is no single country whose fall would have the same impact today.

The world becoming more connected has accelerated us forward—and this, to an often-under-recognized extent, has ended humanity’s periodic moves backward.

QUICK TAKES

Big Blue goes small

IBM just unveiled its 2-nanometer chipmaking technology.

The technology could be as much as 45% faster than the mainstream 7-nanometer chips in many of today's laptops and phones and up to 75% more power efficient, the company said.

That’s utterly mind boggling. For comparison, a sheet of paper is 100,000 nanometers thick. And a strand of DNA? About 2.5 nanometers.

Expect to see breakthroughs in everything from video quality to language processing to AI efforts such as battery technology and drug discovery.

Don’t flip out over Flippy

Flippy is the ridiculously cute name for a robot that will replace the kitchen staff at fast food restaurants. White Castle has signed up to be the first chain to try it out. According to their Vice President Jamie Richardson:

We're looking at Flippy as a tool that helps us increase speed of service and frees team members up to focus more on other areas we want to concentrate on, whether that's order accuracy or how we're handling delivery partner drivers and getting them what they need when they come through the door.

Richardson’s point is profound. We talk about automation eliminating jobs. But what it actually does is free up human labor for different, more valuable jobs.

Morning Brew just launched a series on automation that explains some of the dynamics. For example, sometimes automation can expand employment in the very industry that automates:

James Bessen said that when labor-saving tech expands work, it’s often “the demand story” at play, a version of which goes something like this: You partially automate the production of a good or service, and it becomes cheaper to produce it at equivalent or higher quality. As a result, that good or service becomes more appealing and accessible to more people, and demand for the product increases.

In some cases, demand increases so much that it results in the expansion of productive capacities—and that can offset any tech-driven job losses, because humans still need to manage certain parts of the process. The famous example here is the bank ATM.

Probably more important, automation often creates entirely new jobs.

More than 60% of jobs performed in 2018 had not yet been invented in 1940, according to a 2020 MIT report that [MIT economics professor David] Autor co-authored. Tech-focused roles, like computer engineers, are well-represented among jobs created over this period, but as incomes rose new personal services (e.g., fitness coaching, mental health counseling) emerged as well.

We have a lot of problems to solve—but a future without jobs isn’t one of them.

Take one Crispr and call me in the morning

Crispr is a breakthrough gene-editing technology has been seen mostly as a way to tackle rare disorders. But now it seems like it’s on the verge of doing much more.

In the next decade, Crispr-Cas9 and other new gene-editing techniques may protect the health not only of [people] with familial hypercholesterolemia but millions of people with a range of conditions, including chronic pain and diabetes. Rather than take drugs for years or even decades, for example, at-risk people might be able to protect themselves with a one-and-done Crispr therapy.

The Wall Street Journal gives this example of a participant in a Crispr trial:

Before participating in a Crispr trial, Victoria Gray, 35, a sickle cell patient from Forest, Miss., suffered severe pain that put her in the hospital more than six times a year. “My life was full of pain,” she says. Now, more than 18 months later, she says she hasn’t suffered a pain crisis or needed a blood transfusion. “I call myself cured,” she says.

The article goes on to warn that these trials are still in their early stages, and that it will take years to identify the long-term benefits and side-effects. But on the whole, the future of medicine looks bright as researchers continue to discover new applications for these revolutionary technologies.

Globalization in a needle

Here’s an eloquent illustration of how connection promotes progress:

Last week, I got a shot of globalization injected directly into my arm. I was privileged (there is no other way to say it) to receive my second dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine—a medicine with 280 different components, manufactured in 86 different sites across 19 countries, driven partly by the research of a son and daughter of Turkish migrants to Germany. That’s globalization in a needle.

Two thoughts. First, this actually understates the point. For example, the creation of the mRNA vaccines as the product of a global, decades-long research effort.

Second, “globalization in a needle”…if I ever come up with a phrase that brilliant, I’m going to retire.

The future of color

TVs went from black and white to color in the 1950s. Since then, the pictures have become sharper, the screens wider and flatter, but color is color, right? Wrong. Turns out, everyone’s favorite movie studio, Pixar, has plans to revolutionize the way we enjoy color, too.

In a riveting piece for Wired, author Adam Rodgers heads over to Pixar’s offices to view a cut of Inside Out different from the one we’re all familiar with. The story is the same. But the color?

The red archway around the staircase is the most vivid red I have ever seen, and when Joy and Sadness start walking down the stairs, the edges of the screen disappear. The room, the world, is nothing but black except for the stairs. The balloons of Bing Bong's prison look unearthly, like a Jeff Koons dog with eldritch powers. “I want to say 60 percent of this frame is outside the gamut of traditional digital cinema,” Glynn says. “We have a version of this film that has been creatively approved and built for exhibition on televisions that don't exist yet.” You can see them only if you saw Inside Out in a fancy-pants Dolby-equipped theater.

You can't buy these colors for your house. But Pixar does have a prototype of what that TV might be like. . . .

Once these technologies are in every movie theater and every living room, maybe even on every phone, things are going to get really weird. They will test the limits of human color perception and maybe even extend them. Poppy Crum, the neuroscientist who runs research at Dolby . . . says her research shows that these tricks of light heighten the entire emotional experience of moviegoing.

As exciting as advances in health and computer technology and space travel are, there’s something uniquely inspiring about the fact that we live in a world where great minds can take something that seems impossible to improve—and make it better.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Creativity, Inc. by Ed Catmull

Ed Catmull co-founded Pixar and helped build it into the transformational movie studio responsible for Toy Story (the first full-length computer animated film), Finding Nemo, Up (my personal favorite), and countless other gems. (They were also responsible for Cars, Car 2, and Cars 3, but we can safely ignore those abominations.)

This book tells the story of Pixar, with a focus on the lessons Catmull learned about how to instill creativity into the culture. For instance, we learn that the essence of Pixar’s creative process is to go “from suck to non-suck”:

[E]arly on, all of our movies suck. That’s a blunt assessment, I know, but I make a point of repeating it often, and I choose that phrasing because saying it in a softer way fails to convey how bad the first versions of our films really are. I’m not trying to be modest or self-effacing by saying this. Pixar films are not good at first, and our job is to make them so—to go, as I say, “from suck to not-suck.” This idea—that all the movies we now think of as brilliant were, at one time, terrible—is a hard concept for many to grasp. But think about how easy it would be for a movie about talking toys to feel derivative, sappy, or overtly merchandise-driven. Think about how off-putting a movie about rats preparing food could be, or how risky it must’ve seemed to start WALL-E with 39 dialogue-free minutes. We dare to attempt these stories, but we don’t get them right on the first pass.

It's inherently difficult to spot good ideas. But the challenge grows by an order of magnitude when you keep in mind that even the best ideas start off looking a lot like bad ideas. Encouraging innovation means working to distinguish between something that isn’t working—and something that won’t work.

But, as Catmull points out, you can never get to the point where you know for sure in advance whether an idea is good or not. Failure, he stresses, is inherent in the pursuit of success. And the right attitude is to minimize the costs of failure and to maximize the learning failure can bring. For instance, there’s this tidbit.

Left to their own devices, most people don’t want to fail. But Andrew Stanton isn’t most people. As I’ve mentioned, he’s known around Pixar for repeating the phrases “fail early and fail fast” and “be wrong as fast as you can.” He thinks of failure like learning to ride a bike; it isn’t conceivable that you would learn to do this without making mistakes—without toppling over a few times. “Get a bike that’s as low to the ground as you can find, put on elbow and knee pads so you’re not afraid of falling, and go,” he says. If you apply this mindset to everything new you attempt, you can begin to subvert the negative connotation associated with making mistakes. Says Andrew: “You wouldn’t say to somebody who is first learning to play the guitar, ‘You better think really hard about where you put your fingers on the guitar neck before you strum, because you only get to strum once, and that’s it. And if you get that wrong, we’re going to move on.’ That’s no way to learn, is it?”

But the most basic advice Catmull gives is that to build a creative team you need to pick great people and then trust them:

Trusting others doesn’t mean that they won’t make mistakes. It means that if they do (or if you do), you trust they will act to help solve it.

There’s a lot more of value in the book—including some fascinating insights about Steve Jobs, who bought Pixar in 2006; and the striking contrast between Pixar at its height and Disney at its nadir. Throughout, the core message is that human creativity—that is, human ingenuity—is the source of great ideas and great products. But human creativity has to be nurtured. Catmull’s book teaches us a lot about how to nurture it.

Until next time,

Don Watkins

P.S. Want to support our efforts? Forward this email to a friend and encourage them to sign up at ingenuism.com.