Immigrating to Ingenuism

Ingenuism Weekly 15

“Chance favors the connected mind.” ―Steven Johnson, Where Good Ideas Come from: The Natural History of Innovation

MEDIA

Can money buy progress?

On the Silicon Valley Explored podcast, Robert Hendershott and Don Watkins discuss China’s failure to buy its way to semiconductor dominance, the new space race, and the value of in-person connection.

INSIGHT

Immigrating to Ingenuism

Don Watkins and Robert Hendershott

Elon Musk famously immigrated to America because “It is where great things are possible,” adding, “I am nauseatingly pro-American.”

Musk isn’t unique, of course. As a recent working paper on global talent flows notes, “More than half of the high-skilled technology workers and entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley are foreign-born.” The authors of that paper—Sari Pekkala Kerr, William Kerr, Çağlar Özden, and Christopher Parsons—go on to observe:

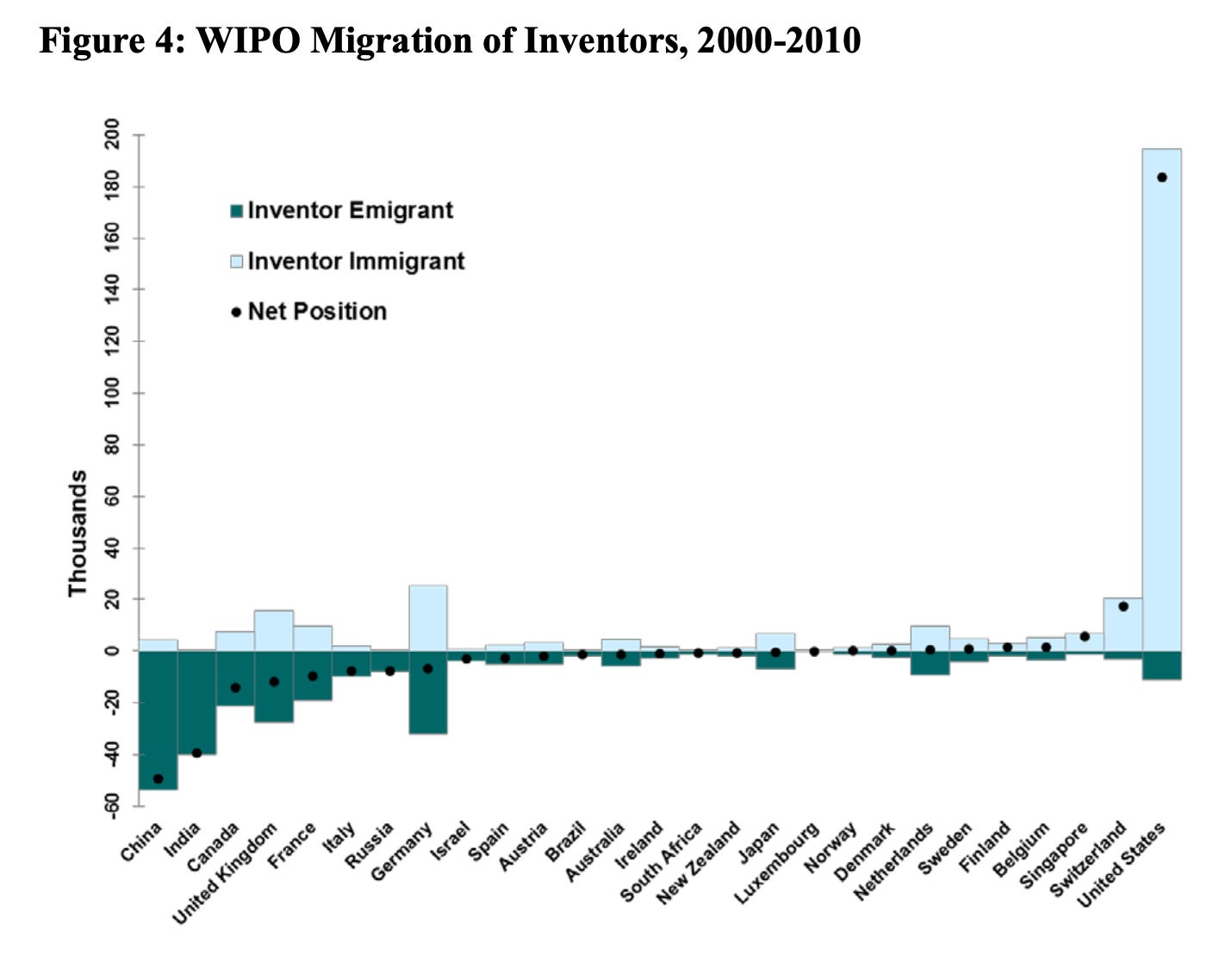

The United States has received an enormous net surplus of inventors from abroad, while China and India have been major source countries. Some countries like Canada and the United Kingdom are major destinations but still experience a negative net flow due to even larger emigration rates for inventors, usually to the United States.

These and facts like these are striking because they amount to sworn testimony by innovators about the key ingredients that make innovation possible. And as Ker et al. point out, chief among the ingredients innovators are seeking out is connection—or, in their words, agglomeration effects:

[M]any high-skilled occupations show agglomeration effects, where an individual worker’s productivity is enhanced by being near to or working with many other skilled workers in similar sectors or occupations. Indeed, in the presence of agglomeration effects, high-skilled migration need not diminish the returns to skills. In fact, due to agglomeration effects, a surge of high-skilled migration increases the incentive for other high-skilled workers to migrate to the same location.

Connection is not all-or-nothing. Connection is the degree to which people are able to share knowledge, insights, and ideas and to collaborate to create something new. The Internet vastly increased our ability to access knowledge, share insights, and propagate ideas. Zoom has made it easier to collaborate remotely. But technology has not eliminated the value of being in the room with colleagues, of living in a community where serendipitous encounters can spawn new companies, of being a short drive away from capital and competitors.

“Great things are possible” in America generally and Silicon Valley specifically because there is a cluster of minds tightly connected—and an environment that supports the ability of people to explore and execute new ideas.

Note, in this regard, that immigration tends to move from less free to more free countries, from less dynamic nations to more dynamic nations, from places that restrict experimentation and penalize failure to places that embrace both. Connection doesn’t help if you’re stuck in an environment where you can’t make use of the knowledge and insights available to you. And being connected exposes people stuck in an unsupportive culture to what’s possible in a supportive culture. It’s no surprise they move!

As technology has made the world more connected, high-skilled immigration has accelerated: “There were about 28 million high-skilled migrants residing in OECD countries in 2010, an increase of nearly 130 percent since 1990. By comparison, the growth rate for low-skilled migrants in the OECD countries from 1990 to 2010 was only 40 percent.”

The more connected the world, the more minds will be empowered to contribute to human progress—and many of those minds will seek out the best environments for innovation available to them, to the benefit of us all.

QUICK TAKES

Connection at a distance

Considering that we just discussed the benefits of in-person connection, it’s worth stressing the value of connection at a distance. In his most recent Substack, Matt Clancy explains how academia is pioneering successful innovation by distributed teams.

Matt notes that distributed teams are becoming much more common in academia. He then takes a deep dive into research about the benefits (or lack thereof) of in-person collaboration, concluding:

I think proximity was (and perhaps still is) important for forming collaborative working relationships, but these relationships remain productive even when academics are far away from each other. At least, this is increasingly the case.

But at the same time, I think there’s another factor that increasingly pushes academics to collaborate remotely. That is the ever-rising set of knowledge needed to push the frontier, which academics are responding to by drilling into ever narrower specialties and forming teams of specialists to tackle research projects. When academics specialize more and more, it becomes ever less likely that the specialty you need to complete a project happens to reside in the same department. . . .

Over time, falling travel and communication costs have increasingly favored building those teams by turning to remote colleagues with the right specialization.

My read: all else being equal, in-person connection is somewhat superior to connection at a distance. But all else isn’t always equal! In a world where it’s easy to connect with distant colleagues, and where colleagues are increasingly specialized, it often makes sense to Zoom, email, and take the occasional flight rather than work with whomever happens to be in your backyard.

Fly me to the moon

Richard Branson can rightfully claim the title of humanity’s first space tourist.

The British entrepreneur beat fellow billionaire Jeff Bezos to the edge of space. Mr. Bezos is set to embark on his own space flight later this month aboard his Blue Origin LLC’s rocket. The two men are part of a new generation’s space race, both attempting to expand access beyond the reach of government and research missions—at least to a handful of high-net-worth individuals who can afford it.

Most of the stories have derisively stressed that space tourism is so expensive that only the rich can afford it. But that’s true of most new inventions, from cars to computers. What’s notable about Branson, Bezos, and Elon Musk is not that they are enabling wealthy individuals to reach space—but that their goal is to make space travel affordable.

By itself, that’s a huge positive for humanity. But what I find most thrilling are all of the spillover effects that the new space race will almost certainly create. NASA’s space race helped spawn everything from artificial limbs to wireless headsets to LASIK. Who knows what amazing innovations will come from trying to bring space within the reach of every human being?

Silicon Valley comes to town

The tech revolution was made possible by concentrated connection: Silicon Valley brought together many of the best entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, and engineers in the world.

But following the pandemic, AOL founder Steve Case argues we’re about to see a tech diffusion, as Silicon Valley emigrants disperse throughout the country and use their talents to solve new kinds of problems.

Many have noted that talent and capital are starting to move out of the nation’s three major tech hubs and into various more affordable cities like Phoenix, Salt Lake City and Tulsa, Okla. But most are missing the more important point: The nation’s tech workers likely won’t work on the same kinds of projects that dominated their time when they were ensconced in their hubs. Entrepreneurs who previously worked in tech bubbles—places that have produced far too many photo-sharing apps—will suddenly be exposed to a wider range of real-world challenges that they likely would never have encountered without the pandemic. . . .

Challenges in fields ranging from healthcare to farming, from transportation to housing, will require subject-matter expertise that many would-be innovators and entrepreneurs often don’t have. Their success will hinge largely on the relationships they forge with people who weren’t their neighbors on the coasts. New ideas will flourish as a result of the relationships among tech employees, executives and investors who become woven into noncoastal locales. And the strength of those bonds will attract investors and partners to any budding venture.

I think of it this way. Deep connection in Silicon Valley created the capability and infrastructure necessary for tech to be able to impact every field. Now the diffusion of tech talent will create new forms of connection that can apply tech’s capability and infrastructure to new areas of human life. Super cool.

A quantum leap in energy

It’s about time. China is building the world’s first small nuclear reactor.

Launched by China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC), the multipurpose modular small reactor technology demonstration project will have a power generation capacity of 125,000 kilowatts. After its completion, the annual power generation will reach 1 billion kilowatt hours, meeting the needs of 526,000 households.

For comparison, the average turbine can meet the needs of about 460 households.

Meanwhile the US government wants Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin and other private companies to create nuclear-powered spacecraft.

NASA and the Energy Department awarded three $5 million contracts to produce reactor-design concepts that could be used to ferry people and cargo to Mars or propel scientific missions to the outer reaches of the solar system, the space agency said in a statement Tuesday. . . .

Nuclear propulsion systems are more efficient than standard chemical-based rockets, meaning they hold promise for traveling faster for more ambitious missions, deeper into space, according to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Go nuclear or go home!

RECOMMENDATIONS

Empire Builders by Burton W. Folsom, Jr.

One of the questions we think a lot about is: what made Silicon Valley, Silicon Valley? Answering that question has two major aspects. First, what distinguishes Silicon Valley from places that aren’t as innovative? And second, what does Silicon Valley have in common with other innovative places?

One place to look is somewhere no one associates with innovation today: Michigan. That wasn’t always the case. From the late 19th to the early 20th century, Michigan helped propel the United States into the most productive economy in the world.

In Empire Builders, historian Burton W. Folsom, Jr. sets out to explain Michigan’s success.

What can’t explain that success, he argues, is Michigan’s climate and natural resources. “In 1850, the young state of Michigan was cold, remote, and swampy.” What’s more, many of the entrepreneurs who drove Michigan’s rise “created products from resources available that had nothing to do with Michigan.”

Nor was Michigan flush with capital for new and expanding businesses. Indeed, raising capital was the big challenge faced by Michigan entrepreneurs.

John Jacob Astor made his money in New York and plowed it into Michigan. Henry Crapo forged a complex network for wheedling capital from his cautious friends in New Bedford and Boston, Massachusetts. Herbert Dow lobbied established businessmen in Cleveland for his capital. Will Kellogg needed help from a large investor in St. Louis.

It wasn’t until the early 1900s that Michigan’s growing prosperity started a flywheel effect, with past success making capital more easily available to launch future enterprises.

In Folsom’s judgment, the key ingredient in Michigan’s rise was freedom:

From the time Michigan entered the union in 1837, the governor and the legislators wanted to make the state an economic powerhouse. Their first effort was to enlist massive government aid in building railroads and canals throughout Michigan.

When this experiment with state control failed, they tried free enterprise and individual liberty. They sold the railroads to private owners and, when that succeeded, they wrote a new constitution that opened Michigan to entrepreneurs and barred the state from intruding on private enterprise. Michigan’s future would be in the hands of its entrepreneurs.

There is abundant material in Folsom’s slender book to support this claim, most of it contained in fascinating stories about Michigan’s leading empire builders. But the vignettes end up being unsatisfying to someone who wants to understand the dynamics that produce the equivalent of a Silicon Valley (which, admittedly isn’t Folsom’s purpose).

For example, though we see how the increase in economic freedom within Michigan helps spur its advance, Folsom notes that America as a whole enjoyed enormous economic freedom during this era. So why did Michigan become the Midwest equivalent of Silicon Valley and not, say, Iowa? Freedom emerges as a necessary condition for innovation—but not a sufficient one.

The most important parallels to Silicon Valley would emerge from an exploration of how Michigan became the auto capital of the world. And while Folsom does tell the story of William Durant, who co-founded General Motors, and Henry Ford, he treats these as mostly separate stories. He doesn’t explore how these early successes attracted talent and led to an ecosystem that made it increasingly easy to start auto companies in eastern Michigan—and increasingly difficult for other parts of the country to compete.

Nevertheless, as a starting point for thinking about how connection, exploration, and environment can lead to concentrated areas of innovation, Empire Builders is a worthy place to start.

Until next time,

Don Watkins

P.S. Want to support our efforts? Forward this email to a friend and encourage them to sign up at ingenuism.com.

Great article; I especially loved the “Migration of Inventors” graph. I’m starting to look forward to Thursdays thanks to Ingenuism.

It's a good article, but missing is the important wider point that phenomena like "agglomeration," interconnectedness, spontaneous cooperation, innovation, etc are subspecies of the most important aspect of capitalism - namely, a highly developed division of labor, which should be known as the "division of production." (H/T to Harry Binswanger for coining that term.) All progress, both material and intellectual, depends on an increasingly specialized and flexible division of production. Division of production is the source of the "cooperative knowledge" that is found only in a free society. In the hierarchy of the factors required for human flourishing, the freedom to associate and specialize stands above individual technical genius.