The Miracle of the 21st Century

Ingenuism Weekly 2

“[I]nnovation is itself a product, the manufacturing of which is a team effort requiring trial and error.” –Matt Ridley, How Innovation Works

ESSAYS

Thanks to everyone who posted feedback and questions in response to our essay, “Ingenuism: A New Theory of Innovation.” A few quick replies:

“Good article, though I am not sure we have a good measure of economic activity since government spending is included in the GDP and tends to throw things off.”

Response: GDP per capita is far from a perfect way to measure human well-being. But this is mainly because it understates progress. What GDP captures is what’s spent on final goods—not the value of those goods. How much do you value the COVID-19 vaccine, or Zoom, or the gasoline that gets you to the hospital in an emergency?

“Isn't the point about Silicon Valley (with the emphasis on ‘silicon’) that it did great things back when Intel and Hewlett Packard were young and growing, but today they and many other US silicon focused companies are either gone or struggling. What changed? The short answer is: what made these Silicon Valley companies successful was misunderstood and hated.

“In the place of the old guard, a new generation of silicon focused companies like Apple, AMD, Qualcomm and TSMC (in Taiwan) have taken over. Will the new guard survive and thrive? That depends on what how they address the same issues that faced the old guard before them.”

Response: There’s a lot to say about the evolution of Silicon Valley and tech more broadly. We look forward to saying some of it! And while the culture’s attitude toward tech and business generally is relevant, a lot of what’s happened is rooted in the very nature of progress. New companies create new innovations that existing companies can’t compete with. High churn among successful companies is precisely what we should expect in an industry that’s rapidly advancing.

“You wrote: ‘Admittedly, continuing challenges remain, from extreme poverty in parts of the world to the impact of rising CO2.’ Does this mean that you guys fear something more than manageable moderate warming? Or what exactly does this refer to? Just curious.”

Response: Our point was that CO2 likely has a climate impact, and regardless of whether you think that impact will be small or substantial, the best way to address climate challenges is through technology and innovation—not authoritarian restrictions.

“If I may contribute an idea: maybe it’s worth discussing how the precautionary principle has a negative effect on innovation.”

Response: Definitely. You cannot understand tech policy without understanding the precautionary principle. And you cannot define good tech policy if you adopt precautionary principle thinking across the board. (See below for my review of Permissionless Innovation, which is all about this issue.)

“You wrote: ‘include a world where 7 billion minds can collaborate to invent and solve vital problems. That's quite a stretch. An optimist would say that perhaps 20% of the population can innovate. The true number is closer to 3%. Innovate means come up with an idea and materialize it. Good ideas by themselves are not innovations.”

Response: That last point is true. What we’re saying is that the more people are connected, the more innovation we’ll enjoy. (3% of a large number is more than 3% of a smaller number!) The limitation on worldwide collaborative innovation is no longer connectedness—it’s policy that holds back potential innovators around the globe.

INSIGHT

The Miracle of the 21st Century

Robert Hendershott

There has been no shortage of transformative innovation in the 21st century. Smart phones, social media, blockchain and cryptocurrencies, and CRISPR gene editing are all changing the world. But we’ve also seen an even more foundational change, one that has made these leaps forward possible.

In the past 20 years, the world has become connected in powerful ways that supercharge progress.

In 1999, the World Wide Web was a vast trove of information—but that information was largely inaccessible. Google’s valuation: $50 million. Today, much if not most of the world’s information is at our fingertips. Google’s market value: $1.3 trillion.

In 2001, Amazon was an online retailer worth $3 billion struggling to build a set of common infrastructure services for internal use. This effort evolved into Amazon Web Services, and today Amazon has a market value of $1.6 trillion.

In 2001, Apple was a niche computer company worth $5 billion. Today, after launching the iPod, the iPhone, and the iPad, Apple has a market value of $2.2 trillion.

Dozens of other technology companies have produced corresponding results, albeit measured in hundreds of billions rather than trillions of dollars. This is the miracle of our time: the level and speed at which innovation has created unprecedented economic value.

Inside the Ingenuism framework, the unprecedented value creation over the past twenty years can be traced back to the 21st century being a time of unparalleled connection—and Silicon Valley (defined as a way of doing business, not a geography) learning how to capitalize on these new capabilities. More specifically, Google, Amazon, and Apple each represent a keystone that supports the miracle of the 21st century.

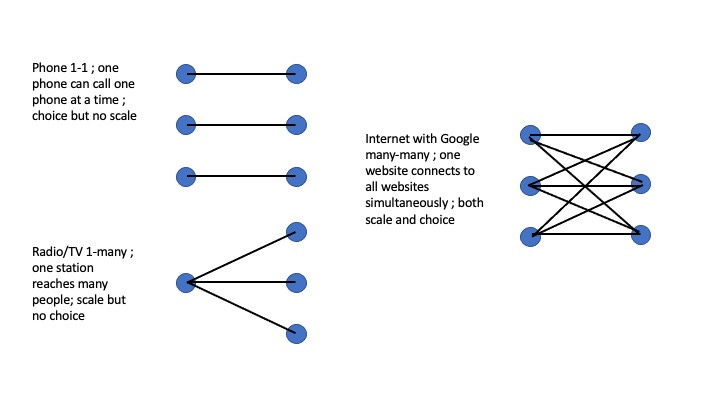

Although the Internet and World Wide Web are seminal technologies for connecting people, they don’t represent a break with the past, but a continuation of a centuries-long trend. Before the Internet, people either connected one-to-one in both directions (e.g., telephone) or one-to-many on one direction (e.g., television).

The early web created the potential for many-to-many connections in both directions. But reality fell short. With no effective way to navigate the morass of content, most users ended up depending on portals—aggregation and curation sites—to find their way around. The web was a long tail of content without an effective search function, making the long tail largely inaccessible.

Google changed all that with their PageRank algorithm. PageRank provided a way to quantify the importance of a web page to effectively direct searchers to the content they would find useful. A world of information opened: now people were truly connecting many-to-many. Everyone has access to everything at all times.

Challenges accompanied this new level of connection. While web users across the globe were able to find niche content, they could also overwhelm the resources of mass market content. Just as a thousand people showing up at Dunkin’ Donuts at the same time would get the place shut down by fire marshals, millions of people trying to access a website at the same time could cause servers to crash: success could kill you! For example, the first broad-based social network, Friendster, acquired three million users in just a few months, overwhelming the company’s resources and frustrating users who couldn’t access the site. Connection was wide but shallow.

In the background, Amazon was dealing with exactly this problem as usage would spike during the holiday shopping season. Their solution, AWS, was rolled out to external customers in 2006 and created modern cloud computing. This made connection deep and robust. So when Zoom usage skyrocketed in March of 2020, resources were able to follow demand. Essentially, the computing resources that would have been used managing, say, airline and hotel reservations were able to be redeployed to keeping people connected to their jobs, schools, and families during a pandemic.

The fact that connection is now wide and deep opens up a new level of potential collaboration, both in ideas and activities. Apple’s iPhone, for example, combines dozens of different technologies into a single elegant design, with elements coming from dozens of different countries. Managing the iPhone’s complex supply chain would be impossible without the level of connection available in the 21st Century.

In a world with wide, deep connection there is more opportunity to 1) innovate by combining other innovations in creative and useful ways and 2) collaborate to build innovative supply chains that make the technology inexpensive and widely available.

We know—iPhones are expensive! But compared to the capabilities it represents—combining what would have previously been a laptop computer, a cell phone, a high-end digital camera, an entertainment center, a GPS system, just for starters—a smart phone is amazingly cheap.

This is the miracle of the 21st Century. Wide connection puts the world’s knowledge and insight at our fingertips. Deep connection allows successful new ideas to spread and scale with demand rather than to fall victim to demand. Collaboration provides access to and empowers the ingenuity of billions. From this arises companies that are enhancing the way millions, even billions, of people do business and live their lives.

QUICK TAKES

Next stop, Graphene Valley

The Wall Street Journal notes that despite the incredible achievements made possible by silicon, it’s “showing its age.”

The reliable biennial doubling in the computational power of microchips, known as Moore’s Law, has been slowing, and could soon come to an end. It’s pretty much impossible, using current methods, to get the elements etched into silicon, like transistors, below about 3 nanometers in their smallest dimension.

That’s bad! But this is no pessimistic warning about technological stagnation. On the contrary, it turns out that we’re creating new materials like graphene, that are even better than silicon.

Collectively, they’re known as 2-D materials, since they are flat sheets only an atom or two thick. . . .

Some of the results of this research can already be found in devices on sale today, but the bulk are expected to turn up over the next decade, bringing new capabilities to our gadgets. These will include novel features such as infrared night-vision mode in smartphones, and profound ones such as microchips that are 10 times faster and more power-efficient. This could enable new forms of human-computer interaction, such as augmented-reality systems that fit into everyday eyeglasses.

Who are you going to believe—the statistics or your lying eyes?

Economist Noah Smith interviews Stripe CEO Patrick Collison about the future of technology, that Great Stagnation hypothesis, and the burgeoning field of Progress Studies.

Notably, Collison argues that if we approach concerns about stagnation by looking at the fields we care about rather than murky statistics designed to measure 20th century progress, we could see far greater progress in the future than the pessimists believe.

[T]o the extent that you're talking about particular macroeconomic time series, you suddenly scope in a whole bunch of definitional and deflator and measurement debates and all that. But if we ignore those and focus on the basic phenomena that we really care about: progress in science, advancement in technology, and the effective deployment of both such that broader societal welfare is enhanced—yes, I would say that I’m certain that we can do very meaningfully better than we are doing today. I’ll claim that we could double our rate of progress.

We agree! Stripe, like Google, took a space that was “handled” and applied key insights to make it much better. Generally, when we think there is a limited potential for progress, it is because we have stopped looking for ingenious ways to improve!

Silicon Valley show trials

Mike Solana gives a rundown of the latest Congressional interrogation of tech executives. TL;DR: it was basically a waste of time.

The circus kicked off with opening statements from select representatives, and there became immediately apparent what would be the tenor of the hearing. Almost every comment, from every congressperson, fell into the category of “technology companies are actually quite evil,” though the sentiment came in a variety of flavors: tech CEOs are responsible for the riot at the capitol (obviously), tech CEOs are responsible for Americans hating each other, there is chaos, for which tech CEOs are responsible, and extremism, wow is there extremism!, and misinformation, and did I say chaos? The viral film Plandemic was cited as the reason Americans are refusing to vaccinate, which is for the record not a thing that is happening. Tech CEOs are responsible for genocide, I learned last week, and the age of “self-regulation” has come “to the end of its road” as, we would later be told explicitly, tech platforms have undermined “the very foundations of our Democracy.”

Mark, your response?

Considering how often Congress is forcing today’s top innovators to attend these show trials, I’m recommending that tech leaders start appointing figurehead CEOs whose only job is to sit quietly while our political leaders mete out tongue lashings in an attempt to go viral.

We’ve got so much ingenuity, we can’t fit it all on earth

Check out this video about how NASA created its Mars helicopter, aptly named “Ingenuity.”

If you build it, they will come and tell you to stop building it

Peter Thiel explains why it takes longer to build things today than in the past—despite our massively expanded knowledge and productive capability. The basic reason why? Regulations are slowing builders down. “You would not be able to get a polio vaccine approved today,” Thiel warns.

So if I copy and paste 11,000 lines from Harry Potter, that’s cool, right?

Speaking of Intellectual Property, the Supreme Court ruled in an important IP case: Google v. Oracle. According to the court, when Google copied 11,000 lines of code from Oracle rather than pay them for a license or write their own code? Yeah, that was fine.

The ruling endorsed Google’s argument that copy and pasting 11,000 lines of code was “fair use” since “fair use is designed to adapt to changing technology and to account for the nature of the copyrighted material.” But as IP expert Adam Mossoff argued prior to the decision: “This argument proves too much. It destroys all copyright protections for all software code, which is always a “changing technology.”

The intellectual property regime that best supports ingenuity is complex—and it’s an important area we look forward to exploring.

Will tech anti-trust lead to tech antitrust?

Trust in tech has collapsed over the past year, according to a survey of 31,000 people in 27 countries. The U.S. saw a decline from over 70% in 2019 to 57% today. This loss of trust makes it far more likely that we’ll see antitrust action against leading tech companies in the near future.

RIP HIV?

Innovation tends to beget innovation. The latest, and most exciting example? The same technology that created the first COVID-19 vaccines are showing promising results in creating an HIV vaccine. “[T]he vaccine successfully stimulated the production of the rare immune cells needed to generate antibodies against HIV in 97 percent of participants.” The vaccine is still in Stage I trials, but so far this is shaping up to be the most effective HIV vaccine to date.

INCREASE YOUR INGENUITY

Write one page a day about whatever happens to catch your attention and you’ll end up with a journal. Write one page a day about a single topic and you’re on your way to a book.

Innovation requires focus. Focus requires saying “no” to everything but what’s most important about your mission. Learn to just say “no.”

RECOMMENDATION

Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom by Adam Thierer

What kind of policies promote innovation, and which hold them back? In this short, accessible book, the Mercatus Center’s Adam Thierer argues for replacing the precautionary principle framework with a framework that treats freedom as a default.

The precautionary principle says that innovations should be held back until they can prove they won’t cause any harm. But that principle, Thierer shows, is itself enormously harmful: it stops or delays countless life-improving innovations.

Instead, the presumption should be “innovation allowed.” Not because technological change poses no risks, but because it carries overwhelming benefits—and we are incredibly good at adapting to the downsides.

Until next time,

Don Watkins

P.S. Want to support our efforts? Forward this email to a friend and encourage them to sign up at ingenuism.com.

Thank you great article