“Progress is more important than perfection.” –Simon Sinek

MEDIA

More value capture, please - Silicon Valley Examined 27

In this episode of Silicon Valley Examined, Robert Hendershott and Don Watkins talk about value creation and value capture, how Web3 is transforming both, and why the pandemic illustrates the importance of creators being able to capture value.

INSIGHT

The virus you want to catch

By Robert Hendershott and Don Watkins

When Hotmail co-founders Sabeer Bhatia and Jack Smith approached the venture capital firm Draper Fisher Jurvetson with their idea for a free email service in 1995, the firm liked the idea but wondered how they would attract users when limited revenues precluded a large marketing budget.

Yet, within 18 months of its July 1996 launch, Hotmail acquired 12 million users while spending a whopping $50,000 on advertising, marketing and promotions. Within 30 months, Hotmail became the world's largest email service, with more than 30 million active members. To put this in perspective, it took Canada almost 400 years to get to a population of 30 million.

How did Hotmail attain this spectacular growth? The company certainly did not invent email. The key moment came when Tim Draper persuaded the company to include a promotional pitch for its Web-based email with a clickable URL in every outbound message sent by a Hotmail user.

Suddenly every email being sent on Hotmail was an opportunity to acquire a new user.

Hotmail’s strategy involved something more than traditional world-of-mouth. Users didn’t have to go out of their way to tell friends and family about a great new email service. Empowered by a newly connected world, Hotmail’s success launched the era of viral marketing: every customer becomes an involuntary salesperson simply by using the product. Even better, the subtle sales pitch comes from with a trusted third party (the sender) and offers a useful product (the recipient is using email, after all, but, in 1996, probably not web-based email) for free!

The result is extraordinarily rapid growth without the company needing to dedicate significant resources.

Leading social networks’ growth follows a similar story.

Consider Facebook: with virtually no marketing the world’s largest social network now connects three billion people, most of whom joined because their friends/family had joined. This cycle repeats itself with WhatsApp, Snapchat, TikTok, etc. Existing participants naturally recruit new users, creating self-propagating exponential growth.

And think about Bitcoin. Sure, today people buy Bitcoin because they hope to make a mint. But the long-term utility of cryptocurrencies depends on their usage. The fastest way for crypto to be adopted into daily life is for people to start offering to pay you in Bitcoin. Are you going to say “no?”

Viral business models can be created or enhanced by incentivizing users to recruit new users. Uber started off with a viral component because people share rides: your friend calls an Uber, you think “what a cool service,” and the next thing you know you are downloading the app. Giving Uber users free rides for signing up their friends takes this phenomenon to another level, accelerating Uber’s (and many others’) growth at a relatively modest cost.

Unprecedented connection in the 21st century makes viral business models possible. But beyond select companies attaining exponential user growth at no cost, connection is how ideas, insights, and innovations spread rapidly to become available everywhere in the world – and produces the exponential progress that is the real virus that we want to spread unchecked.

QUICK TAKES

COVID as a case study

We’ve talked about what COVID-19 teaches us about the future of progress. Matt Clancy riffs on a recent NYT piece about other progress-related lessons.

One reason why connection is so powerful is precisely because of knowledge spillovers. The more widely ideas and insights are shared, the more breakthrough applications are likely.

This is all the more important today, when ultra-specialization (generally a good thing!) means that creators are often more siloed than ever. Connection complements exploration—results that don’t work in one area end up making critical contributions in another. The more people you have doing interesting things and working on interesting questions, the more opportunity there is for unplanned innovation emerging from surprising sources.

Speaking of COVID lessons, did you know that in 2019 some people were asking whether Moderna was “the next Theranos”? One reason why we want to be careful about what we do to prevent “the next Theranos.”

The abundance agenda

Also peaking of COVID lessons, Derek Thompson uses the policy failures surrounding COVID-19 testing to make a wider point: the need to make abundance a national priority.

The problem:

Zoom out, and you can see that scarcity has been the story of the whole pandemic response. In early 2020, Americans were told to not wear masks, because we apparently didn’t have enough to go around. Last year, Americans were told to not get booster shots, because we apparently didn’t have enough to go around. Today, we’re worried about people using too many COVID tests as cases scream past 700,000 per day, because we apparently don’t have enough to go around.

Zoom out more, and you’ll see that scarcity is also the story of the U.S. economy. After years of failing to invest in technology at our ports, we have a shipping-delay crisis. After years of a deliberate policy to reduce visa issuance for immigrants, we suddenly can’t find enough workers for our schools, factories, restaurants, or hotels. After decades of letting semiconductor-manufacturing power move to Asia, we have a shortage of chips, which is causing price increases for cars and electronics.

Zoom out yet more, and the truly big picture comes into focus. Manufactured scarcity isn’t just the story of COVID tests, or the pandemic, or the economy: It’s the story of America today. The revolution in communications technology has made it easier than ever for ordinary people to loudly identify the problems that they see in the world. But this age of bits-enabled protest has coincided with a slowdown in atoms-related progress.

The solution:

In the past few months, I’ve become obsessed with a policy agenda that is focused on solving our national problem of scarcity. This agenda would try to take the best from several ideologies. It would harness the left’s emphasis on human welfare, but it would encourage the progressive movement to “take innovation as seriously as it takes affordability,” as Ezra Klein wrote. It would tap into libertarians’ obsession with regulation to identify places where bad rules are getting in the way of the common good. It would channel the right’s fixation with national greatness to grow the things that actually make a nation great—such as clean and safe spaces, excellent government services, fantastic living conditions, and broadly shared wealth.

This is the abundance agenda.

I view this as highly aligned with the goal of progress, but with a different emphasis.

Both progress and abundance are focused on enhancing human flourishing. Progress emphasizes our enhanced capability: growing knowledge, growing technology. Abundance emphasizes, as Derek puts it, the need “to increase the supply of essential goods.”

In the end, you can’t fully disentangle them since more progress is the primary thing that will deliver an increased supply of essentially goods (and a bunch of new goods that may not even exist yet).

One question is which has more marketing cache: will people sooner get behind a progress agenda, or an abundance agenda?

What came first? The optimist or the case for optimism?

Kevin Kelly makes a compelling case for both general optimism and for why we should be optimistic in the 2020s. The whole thing is worth reading, but this section was especially on point:

For the first time on the planet, all adult beings will be connected together. The penetration of connected devices is likely to reach 100%. This vast connection creates a huge continuous audience, a planet-scale market, and potentially unified global movements. A start-up in a small country has a greater chance than ever of having a vast billion-person customer base. Vast global audiences not only finance mega cultural creations, they also provide hundreds of millions of niche markets, a boon for creators, art, and commerce in any town on the planet. Global commerce increases, the global exchange of culture is enhanced (K-pop and K-dramas everywhere!), and best practices are spread around the globe. Universal connection is a new tool for harnessing the resident genius in 8 billion people no matter where they live.

When all adults on a planet connect, they can cooperate at a scale and speed never before possible. Existing large institutions are also enhanced by this acceleration, while entirely new forms of collaboration are now possible. In the next two decades we will likely witness at least one grand project created by one million people around the globe working together on it in real time -- a feat enabled by universal connectivity. When all 8 billion people are connected together we have more of a chance to prosper together.

Couldn’t have said it better ourselves.

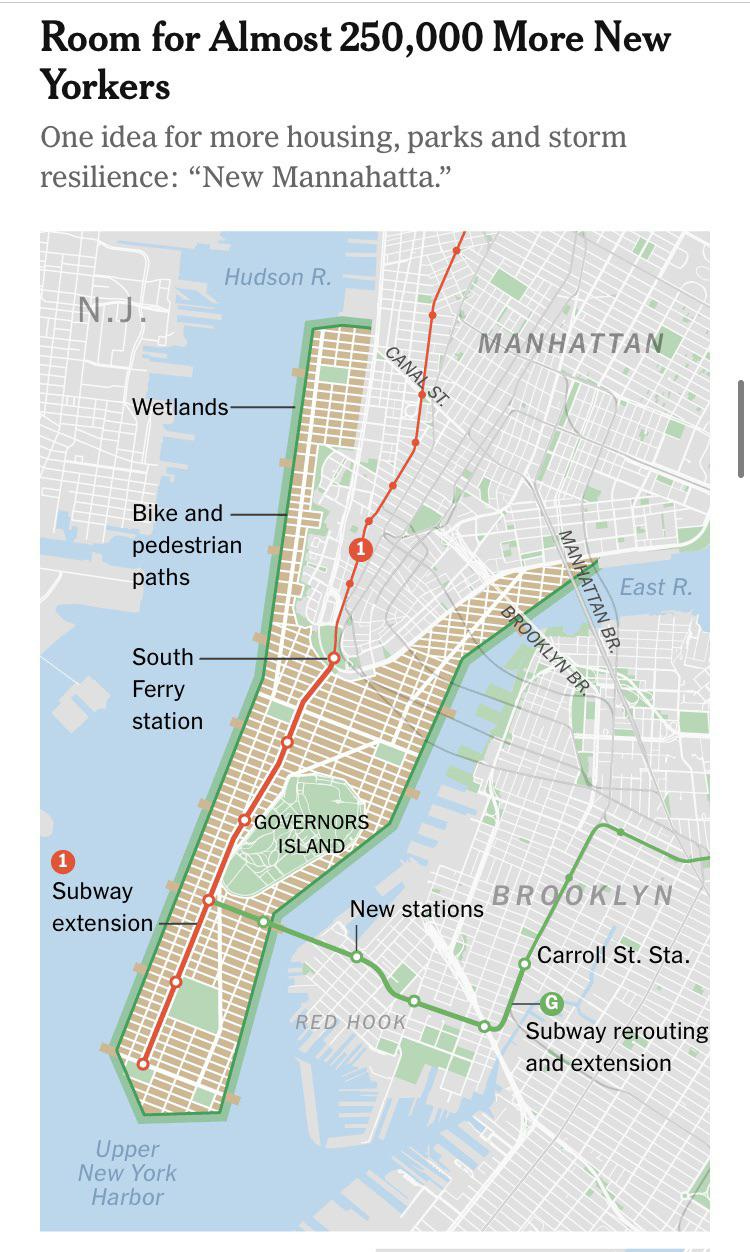

The Manhattan Project

I have no idea how viable this idea is, but culturally this is exactly the kind of thing a pro-progress culture should be discussing: how to expand Manhattan.

From the New York Times(!):

This new proposal offers significant protection against surges while also creating new housing. To do this, it extends Manhattan into New York Harbor by 1,760 acres. . . .

A neighborhood of that size is bigger than the Upper West Side (Community District 7), which is 1,220 acres. Imagine replicating from scratch a diverse neighborhood that contains housing in all shapes and sizes, from traditional brownstones to five-story apartment buildings to high-rise towers. If New Mannahatta is built with a density and style similar to the Upper West Side’s, it could have nearly 180,000 new housing units.

Honestly, this is my new favorite idea.

The hero pig and the human swine

Pigs were already my favorite animal, but I finally feel comfortable arguing that they are objectively the best animal. Because we just had the first successful (so far) pig heart transplant thanks to genetic engineering.

In a medical first, doctors transplanted a pig heart into a patient in a last-ditch effort to save his life and a Maryland hospital said Monday that he’s doing well three days after the highly experimental surgery.

While it’s too soon to know if the operation really will work, it marks a step in the decades-long quest to one day use animal organs for life-saving transplants. Doctors at the University of Maryland Medical Center say the transplant showed that a heart from a genetically modified animal can function in the human body without immediate rejection.

The patient, David Bennett, was terminally ill and so was willing to undergo the experimental procedure.

“It was either die or do this transplant. I want to live. I know it’s a shot in the dark, but it’s my last choice,”

I wish him the best. For his sake and for humanities. As one scientist noted, “If this works, there will be an endless supply of these organs for patients who are suffering.”

But of course the story wouldn’t be complete if some anti-humanists didn’t object:

Animal rights groups like PETA oppose xenotransplantation, both on the grounds of animal cruelty and the potential for spreading disease.

Sorry, not sorry.

Until next time,

Don Watkins

P.S. Want to support our efforts? Forward this email to a friend and encourage them to sign up at ingenuism.com.